Mary Sherafati, Writing Consultant

Our staff often engage in other creative processes as part of their learning and writing. In this week’s blog post, Mary Sherafati discusses how she finds practicing her painting skills similar to the process of becoming a stronger writer. Check out her journey and her paintings below!

Before beginning my academic journey into the world of writing, I tried to improve my painting as I have always dreamed of being a good painter. I therefore took my first painting classes in 2015. First, I was in a hurry to make a name for myself as a good painter; however, gradually I reckoned that in order to become a good painter not only do I need to be more and more patient but also I need time. I need time to learn, to practice, and to make mistakes several times. I also learned that to be a good painter, I should not be afraid of receiving feedback, either positive or negative.

One of the most important processes in creating a picture is brainstorming. At first, I could not do it alone. For example, I looked at a flower, and wanted to draw it, but I did not know how to start, I felt stressed out and started to blame myself thinking that I’m the least talented person in painting. Since I loved painting and felt enthusiastic to progress, I talked to my painting teacher. She helped me, then, with brainstorming. For example, she taught me a technique through which I first see the pictures in geometric shapes including circles, squares, triangles as well as rectangles. Through this technique, my fear was removed gradually. She continued teaching this way to assist me in making an outline before the main step of painting. She wanted me to draw all the geometric shapes that I saw in the picture on my paper without being worried about the result. It was awesome, as through this way of outlining, I learned how to paint.

I learned that brainstorming and outlining are so important. For example, if I wanted to paint a bird, I draw its head as a circle, its body as a triangle, and its tail as a rectangle. Then, I learned that to make a good picture, I need to receive feedback and I need to draw the same picture several times to make one of the best pictures. I learned that I need to be patient and trust time to improve my painting by experiencing it. I also learned that I should know the genres as well as the techniques for painting and follow specific strategies. For example, for painting with collage technique, you have the combination of reality with painting, or combine a real picture with your painting. In the following picture, the flowers are real, the bird is the amalgamation of my painting and a real picture, and the context and the small pictures on the corners are my own painting:

For cubism and imperialism, on the other hand, I learned that the combination of colors make the picture. It needs lots of practice to recognize how to create art just by mixing the colors. Sometimes, when you look at the picture close by, you might not understand the power of the colors and the painting might look strange, but when you step back, and look at the picture from a little bit far distance, you feel how amazing the picture is. Like the following picture:

When I started my academic journey in writing, my experience of painting helped me a lot. To me, writing and painting follow the same processes. For example, I learned that like painting, I need to brainstorm and create a picture of what I am going to write about. I, moreover, was in the habit of making an outline for my writing. At first, I could not make my outline alone, so I asked for help from my writing teacher. I learned that for making my outline, I should know the genre as well as the context of my writing, and follow a specific technique based on that. These were all tasks I practiced before through my painting classes.

For example, I learned that for some tests like IELTS, I need to write my writing based on the types of questions, and depending upon the types of questions, my writing style should be different, my body paragraphs should be different, and more. For direct questions in IELTS writing tests, I need four paragraphs, whereas for argumentative questions for the IELTS test, I need to have five paragraphs. Gradually, I also learned how to write for class assignments, how to write an article, a book review, or a conference paper. Additionally, what has made my writing and painting experience similar was the process of receiving feedback from more experienced writers and painters, and having several drafts. I learned that to be a good writer, I need to revise my paper several times based on the feedback that I receive. I learned that feedbacks might be positive or negative, but both have been constructive for me so far.

Parallels between painting and writing:

In order to show you how good writing as well as a good painting will be created by being patient and by practicing a lot, I will give you some examples through which I discuss and analyze one of my paintings as well as my writings from my first draft to the final one. During my drafts, I received feedback from my instructors and peer colleagues as well as fellow students.

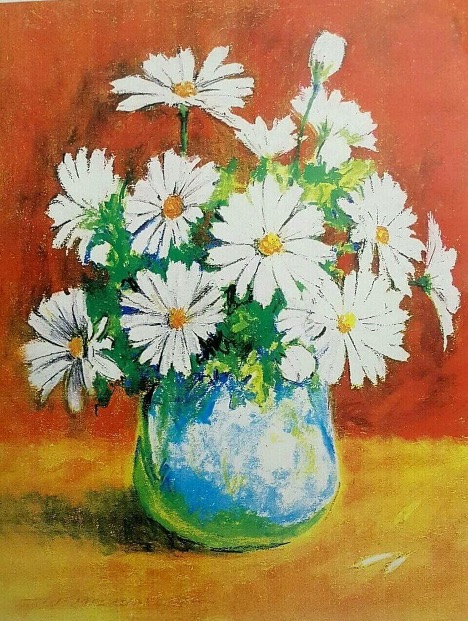

Here is my first draft of painting in which I tried to paint some flowers in a vase:

This draft made my painting teacher frustrated, and she wanted me to paint again. At first, I got frustrated and stopped painting for three weeks; however, I love painting, so I tried to listen to my teacher and go for my second draft:

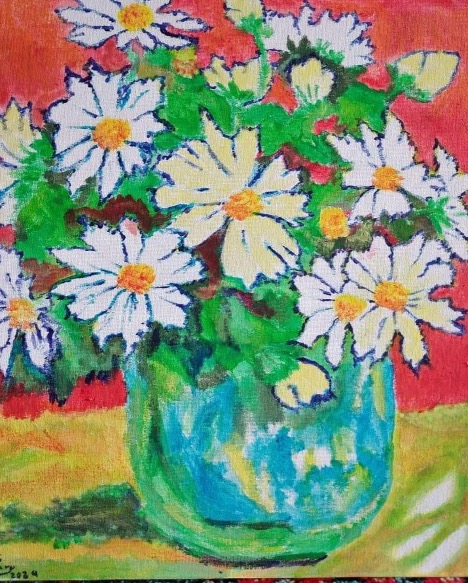

In my second draft, the vase looks good, but the flowers were not still acceptable. This time, both my teacher and I wanted to see what my third draft would be like:

In my third draft, the flowers were seemed better, but the vase was not my favorite. I went for two more drafts as well . Although my teacher could see my progress, she encouraged me to practice more and more and trust time. I started painting the vase and flowers in January, and here is the result of my practice, and being patient and trusting time in March:

As you see, the final version looks much better.

The same also occurred for my writing assignment. I had to write a conference paper. It was about a proper type of feedback in writing in a translingual context. This process of drafting, getting feedback, and revising happened three times before I finally landed on an innovative approach, and I reckoned that I have been the first person to discuss the approach I wrote about in my paper.

As a result, these types of practicing, and having several drafts for my writing and revising my papers based on the feedback I received and my further studying not only helped me achieve an A in my course subject but also made me creative and helped me create something totally new and beneficial. The same is also true for my painting. In the following painting, my teacher only asked me to draw the banana, but I like birds, so I tried to be creative and paint it on top of the banana. I also love the flowers, so I tried to have them all in one picture:

Isn’t my painting interesting?

Conclusion:

In my opinion, and based on my experience as a writer and a painter, in order to be great artists and writers, we need to practice a lot. We should learn that we need to trust the process. We should start with brainstorming, continue with outlining, and then try to cover some drafts. Also, in order to become a good writer, we need to be self-confident and trust time, as my experience shows that if we gradually practice and not give up, we will improve. During our journey, we should not feel ourselves alone and take the role of receiving feedback a lot more seriously. In my opinion, great artists and writers are the ones that share their work with others and ask for feedback. This is why we have art exhibits. This is why we have the Writing Center!

Come see us and share your writing as well as writing concerns with us! I’m sure you will enjoy your meeting with us and see your improvement in writing via the feedback you receive from us.

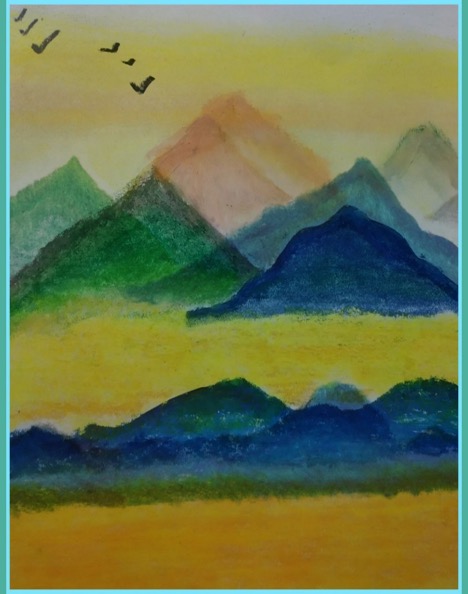

Enjoy some of my other paintings please: